|

Figure 1. The Turner Provincial Cent Leaf Numbering System

|

Figure 3. Broken and Repaired Stems 9 on 1859 Cent Reverses

|

Figure 4. Breakage and Repair of Stems 8 & 10 on 1859 N9 Cents

|

Figure 5. Loop 2 Breakage and Repair on 1859 Narrow 9 Cents

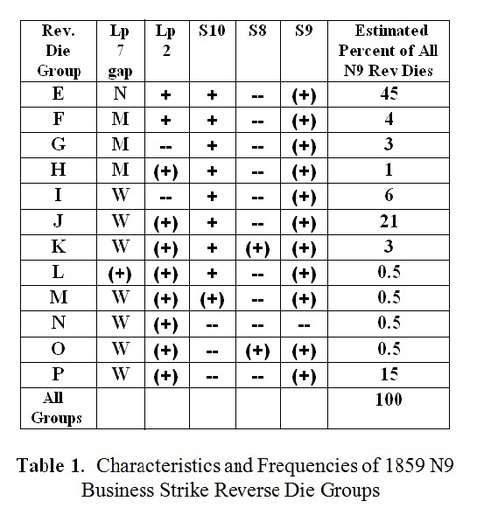

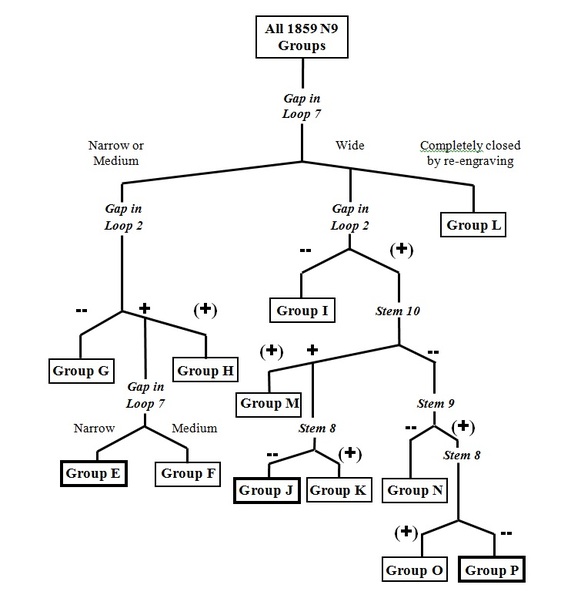

Nomenclature for Individual Dies and Die Pairs The numbering for the reverse dies is based on the device groups presented in Table 1 and Figure 7. Die numbers begin with the capital group letter followed by a number. If a die is part of a reverse die set (two or more reverses linked to a common obverse), then each reverse in the group has the same numerical portion. The first die in the series has no lower case suffix, but each subsequent reverse has a lower case letter suffix. For example, in the E7 die set we have observed three reverses: E7, E7a and E7b, E7 being the first and E7b being the last used. Assignment of the die usage sequence in the above die set was made possible by staging the obverse die; that is, noting deteriorative changes that occurred as a result of its continued use. Such changes could include clash marks, the appearance and progression of cracks and collapses, buckling of the field, wear striations and general blurring of the devices. Some hardy dies have up to ten recognizable stages (or states)! If one chooses to express the state of a die as part of the die name, the die state becomes a numerical suffix. Thus, E7b-6 is die E7b in state 6. The higher the state number, the more deteriorated the die is. Since the Queen’s portrait on the obverse punch did not undergo deterioration like the maple wreath did, the numbering system for the obverses must have a different basis. For the three bridge obverses that share 1859/8 and 1859 Narrow 9 reverses Turner’s designations die designations are maintained: OI1, OG3 and OG4. [1] Serious thought was given to grouping the obverse dies based on repunching patterns in the legend, but at length we decided to make the obverses a single group “o” (for obverse). Following the “o” prefix is a number and sometimes a lower case letter. The lower case letter is used analogously to its use on the reverses. The only difference is that its use is determined by obverse die sets (where a single reverse die shares two or more obverses). Thus, we find that reverse E5 is coupled first with obverse o2, then with a second obverse, which by convention is designated o2a. This brings us at last to the nomenclature convention for obverse-reverse die pairs. It has the obverse and reverse die names separated by a “/”, e.g., o4/E7a. [1] Turner II, pp. 82-85, 88-89. With Rob’s permission. Figure 7. Sorting Scheme for the Reverse Groups of the 1859 N9 Cent

Other Features Which Aid in Attributing the 1859 Narrow 9 Dies Having completed a survey of the device deterioration and its repair on the 1859 N9s, we can now turn our attention to several other features that result from changes in the dies and which can be useful in identifying specific dies. Repunched Letters and Numerals Broken letter, Repunched Repunched Repunched

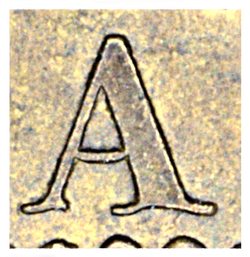

Not repunched (much of original (less of original (Little of original letter showing) letter showing) letter showing) Figure 8. Repunching of the A of REGINA on 1859 N9 Obverse Dies Figure 9. Other Repunched Letters on 1859 Narrow 9 Obverses

Figure 10. Repunched Characters on 1859 Narrow 9 Reverses

Potentially any letter or numeral on the 1859 N9 obverse or reverse dies can come with signs of repunching. The panels in Fig. 8 form a particularly interesting series of examples. In the first panel is something very seldom seen in this series: a defective character that should have been repunched, but wasn’t. The “broken A” occurs on at least six dies. When it was repaired, there sometimes remained telltale signs of the original broken A. In panel 2 these signs are very obvious and in panel 3 they are less so. On the die that struck the coin in panel 4 the A was repunched so skillfully that one can hardly see any sign that it was done. In general the extent to which the repunching of a character is detectable depends on three factors: the number of separate impressions made with the correcting punch, the position of the correcting punch relative to the broken character, and the final depth of the correcting punch impressions. If the correcting punch wasn’t hit hard enough (as was the case in Fig. 8, panel 2), then even perfect punch positioning wouldn’t prevent some evidence of the broken character from remaining. Although repunching details can be very useful tools for die identification, one must use great care. For example, the two repunched Gs in panels 1 and 2 in Figure 9 look alike at first glance, but they are really slightly different and are not from the same die. The reader will find with experience that some repunches occur on many dies (e.g. doubling on the right side of the A in GRATIA) and should essentially be ignored. These cases will be pointed out later in the detailed descriptions of the dies. Die Cracks State 2 State 4 State 5

Figure 11. Progression of Die Cracks on a Provincial Cent Obverse Die Die cracks are an extremely useful tool for quickly zeroing in on the attribution of many 1859 N9 dies, both obverse and reverse. Some dies seem to have been cracked the moment the first coin was struck. More often, cracks develop during use. In any case, once present, cracks tended to continue to extend until the die was retired. A good example of crack appearance and extension can be seen on the R of REGINA on the die illustrated in Fig. 11. In State 1 there is no sign of any cracking. In State 2 a crack runs from a rim denticle to the top of the R, then splits into two small branches to the sides. In State 7, the final stage recorded for this die, all three parts of the crack have enlarged grotesquely and the field as well shows many irregularities. Die Collapses Figure 12. 1859 N9 Cent Showing a Large Area of Die Collapse at the Left

Die collapses are a phenomenon primarily restricted to the Province of Canada cent and largely, though not exclusively, restricted to the reverse. A die collapse is manifested on the coins as a raised area, covering up to 20% or more of the surface. With a well-developed collapse, like that on the coin in Figure 12, wear in the highest areas can be accentuated greatly. There can also be multiple collapses on the same die. We have seen as many as three collapses on a single reverse. One assumes collapses are due to inadequate mixing of the die steel. Whether they are due to air pockets or compression of pockets of contaminants is unclear. In any case, collapses are another useful tool at our disposal for identifying dies. Clash Marks, Rust Marks and Overpolished Areas Figure 13. Clash Marks on 1859 N9 Cents

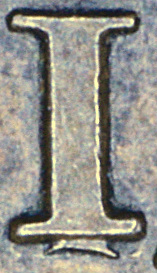

The process by which clash marks arise has long been known to collectors: when the dies come together in the absence of a blank, the opposing surfaces can mark each other. Die clashes are very common of Province of Canada cents. One can take advantage of clash marks in die identification, particularly when they are as spectacular as the examples in Figure 13. In the top panel we see an obverse with multiple, heavy clash marks outlining the vine loops and leaves from the reverse. And in the lower panel the tops of I and A from the REGINA in the obverse die show clearly flanking L 11 (arrows). Die Chips Figure 14. Die Chip Forming a Bridge on an 1859 N9 Cent

[This is a new section that must have text written for it.] Die Clogs Figure 15. Clogged As on an 1859 N9 Obverse

The final feature in this overview is different from the others in that it is not permanent. Die clogs result from material getting into the letters or beads and preventing those parts of the design from fully striking up. Interestingly, some dies have a clog, are cleared and then get a second, different, clog. For difficult dies, clogs can sometimes be helpful in identification. |