SECTION ONE

INTRODUCTION

The Province of Canada cent was produced by the Royal Mint in London over a one year period, from December 1858 until December 1859. It comes in three major date varieties: 1858, 1859 9 over 8 and 1859 Narrow 9. Each has multiple minor die varieties, but this article is mostly restricted to the 1859 Narrow 9 cent varieties. The 1858 and 1859/8 dies have been covered in the writings of Rob Turner, noted elsewhere in this website.

The world of Province of Canada 1859 Narrow 9 cent varieties is a fascinating and sometimes complex one. It contains far more die varieties than any other date of any denomination in the Canadian Victorian series. There’s always something to see on an 1859 cent if you look hard enough. This introductory article is intended to help you understand the nature and scope of these varieties and prepare you to begin cataloging 1859 cents using the Haxby Online Catalog of 1859 Narrow 9 Cent Varieties.

There are two main reasons for the large number of 1859 cent die varieties. The first is the mintage. The total mintage of Provincial cents was 9,690,388, a huge quantity for the time. About 8 million of the total was the 1859 Narrow 9 variety. Second is the method of die production then current. The dies received so much handwork in their finishing that each die became distinguishable from every other, making the coins from each die a distinct die variety. Thus, in our early work (1970s) on the 1859s we recognized that to do an adequate job describing the die varieties of the 1859 Narrow 9s meant describing every die. That is the basis of our online catalog.

Dies and Their Arrangement in the Coining Press

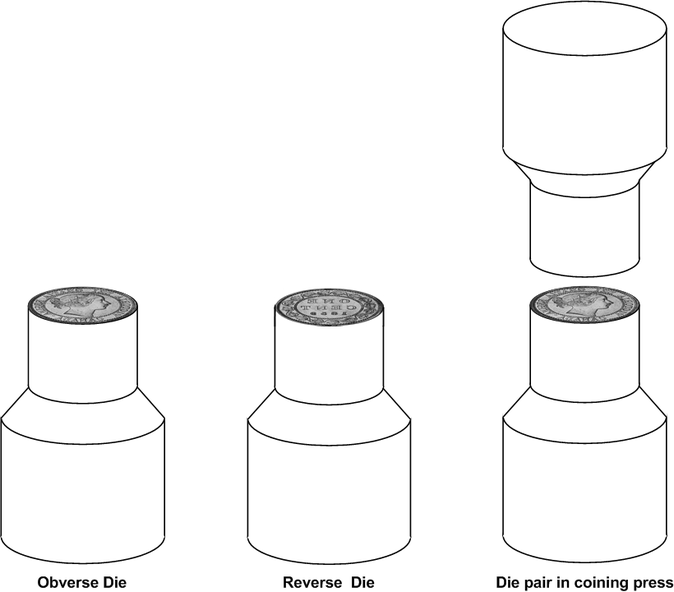

The design of each 1859 cent was struck onto a plain bronze planchet or blank by a pair of steel dies, obverse and reverse, operating in a coining press. The dies were mounted with their faces opposed: the obverse (with Queen Victoria’s portrait) on the bottom and the reverse (with the maple wreath and date) on the top. A third tool (not shown), called the collar, restricted the sideward expansion of the blank during striking and imparted the plain edge to the coin.

Die Usage Practices

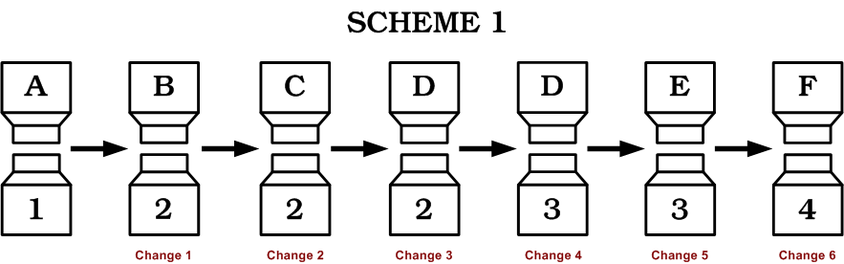

Now, each coin can be said to have arisen from a die pair: a specific obverse and a specific reverse die. When the dies became unserviceable, e.g., because of excessive wear or catastrophic cracking or collapsing, the coining press was stopped and they were replaced with new ones. Scheme 1 below is a hypothetical arrangement of seven successive die pairs in a press. Each arrow represents a press stoppage and a die change, so there are six die changes in this scheme. Obverse dies are designated with numbers and reverse dies with capital letters.

In the first change both dies, 1+A, are removed and replaced with a new pair, 2+B. While this kind of lock step change undoubtedly occurred with the 1859s, it was more common to replace only one of the dies, as shown in the second through fifth changes. For example, in the second and third die changes, obv. 2 remained in the press and new reverse dies were introduced. Only in the fourth change was a new obverse put into the press.

Notice that the die changes in Scheme 1 lead to three kinds of die pair sets:

Notice that the die changes in Scheme 1 lead to three kinds of die pair sets:

|

1.

2. 3. |

Each die is coupled with only one opposing die during its lifetime; i.e., both dies begin use and are retired simultaneously: 1+A.

A single obverse die is coupled with multiple reverse dies: 2+B, 2+C, 2+D, or 3+D & 3+E. A single reverse die is coupled with multiple obverse dies: 2+D & 3+D. |

The predominant kind of die pairing is the second type, where a single obverse is associated with multiple reverses. Indeed, one obverse has been found to have been used with no fewer than eleven reverses! Going the other way, the largest number of obverse dies found coupled to a single reverse is three.

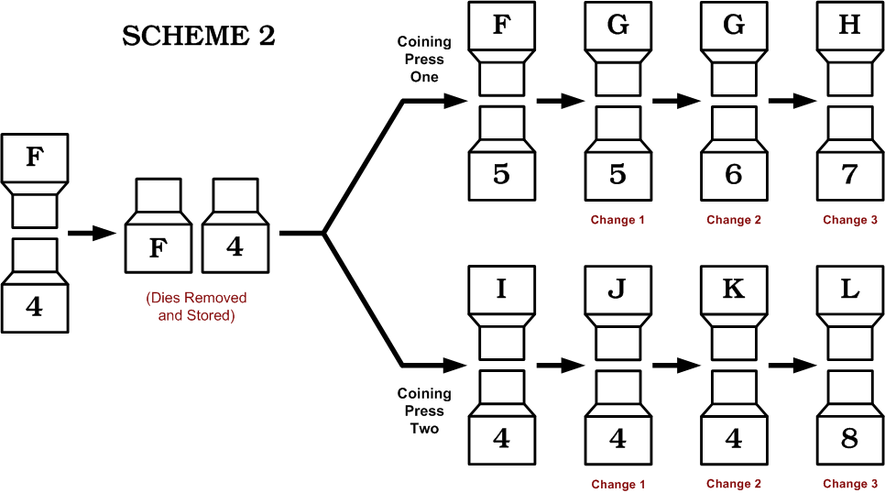

While the three types of die pair sets described above represent the majority of the 1859 die pairings, there is a fourth type. It is the result of a practice that can be called die mixing, as shown in Scheme 2. In the first step both the obverse (4) and reverse (F) dies in an original pair are taken out of the coining press while still in useable condition, stored and later coupled with new mates and continued in use. In our hypothetical scheme members of the original die pair 4+F later ended up in the die pairs 5+F, 4+I, 4+J and 4+K. Currently, only two cases of die mixing have been recorded for the 1859 cents.

Numbers of Dies Used

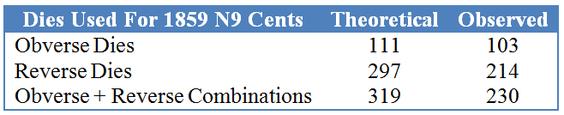

Just how many obverse dies, reverse dies and obverse-reverse die combinations were involved in striking the 1859 Narrow 9s? The table below summarizes our most up to date information.

The theoretical quantities for the obverse and reverse dies come from the original die records, which still survive in the British Archives. About 124 obverse and 336 reverse dies were available for the 1859 Narrow 9 cents, but some 13 obverse and 39 reverse dies were left unused (at least for circulation strikes) and eventually were destroyed. The theoretical number of die combinations is calculated on a proportional basis: (observed combinations/observed reverse dies) x theoretical reverse dies = theoretical combinations.

The large number of dies needed in striking the Province of Canada cents at least partly reflected the fact that the Mint was going into uncharted territory. The planchets were of bronze, a harder metal than copper and they were thinner, providing less of a buffer between the upper and lower die. Furthermore, dividing the theoretical number of reverses (297) by the theoretical number of obverses (111) used, we find that the reverse:obverse die ratio is 2.7:1. Why were so many more reverse dies needed? A major reason must be because in the old Boulton screw presses of that era the upper die tended to wear faster than the lower die with use. It was considered important to preserve the regal portrait as much as possible, so the obverse die got the preferred bottom position. It’s also possible that the nature of the reverse design with its many leaf points fostered more die cracking.

Despite the top position of the reverse die it should not be assumed that any new obverse die would outlast any new reverse die. Die life varied considerably in the mid-19th century. A die could last for only a few thousand impressions or it could strike tens of thousands of coins. But, on average, an 1859 cent reverse die would strike about 27,000 coins and an obverse would strike about 72,000 coins.

The large number of dies needed in striking the Province of Canada cents at least partly reflected the fact that the Mint was going into uncharted territory. The planchets were of bronze, a harder metal than copper and they were thinner, providing less of a buffer between the upper and lower die. Furthermore, dividing the theoretical number of reverses (297) by the theoretical number of obverses (111) used, we find that the reverse:obverse die ratio is 2.7:1. Why were so many more reverse dies needed? A major reason must be because in the old Boulton screw presses of that era the upper die tended to wear faster than the lower die with use. It was considered important to preserve the regal portrait as much as possible, so the obverse die got the preferred bottom position. It’s also possible that the nature of the reverse design with its many leaf points fostered more die cracking.

Despite the top position of the reverse die it should not be assumed that any new obverse die would outlast any new reverse die. Die life varied considerably in the mid-19th century. A die could last for only a few thousand impressions or it could strike tens of thousands of coins. But, on average, an 1859 cent reverse die would strike about 27,000 coins and an obverse would strike about 72,000 coins.